A selection of writings, speeches, photographs and events as well as some of my favourite literary passages.

Thursday, 25 February 2021

Favourite Writing - Brazilian Adventure

Tuesday, 23 February 2021

The Orangery Garden 1998 - 2012

The Orangery was developed from an carpentry shop where they made the stairs and window frames for the houses being built in Wandle Road in the 1890s'. The land was bought by Nicholas Castagli, who did up several houses in the street before developing The Orangery in Georgian style using old pine doors and fittings. We were its first owners.

The house is approached through a tunnel between two houses and is protected by an electric gate. It has its own driveway and a parking area sufficient for two cars. Looking through the gate from the roadside, one couldn't see the house or even the cars, so it was very secluded.

The garden was paved and planted when we moved in.

|

| The entrance to The Orangery between no's 76 and 80 Wandle Road |

|

| The Orangery garden. The houses behind are separated by their gardens from the back of the house |

|

| The Orangery garden in spring |

|

| The Orangery garden in spring - overlooked by two bedroom windows and the study window |

|

| The Orangery - main seating area |

|

| The Orangery - main dining area |

|

| Mahonia, wisteria, choysia and honeysuckle |

|

| The conservatory |

The Orangery 1998 - 2012

The Orangery Drawing Room

The prevailing impression inside the Orangery was one of light and peace. The main room had long windows to the garden and the front door and hall were also glazed.

|

| The hall had double old pine doors |

The drawing room was large enough to be able to place sofas and a desk so that one can walk round them, rather than having to being ranged along walls as in the usual town houses. At the end of the room, we built a conservatory that increased the feeling of light, and was used for entertaining as well as doubling as an artist's studio.

|

| The conservatory with garden beyond |

|

| The kitchen looking into the drawing room. It had old pine doors that were habitually left open. |

|

| The kitchen |

|

| The Study |

|

| Main bedroom |

|

| The second bedroom with its terrace |

|

| Drawing room with paintings and plaster frieze over then fireplace. The set of paintings are by Nobu. |

|

| Looking into the main bedroom |

|

| Painted panel in the main bedroom |

|

| Painted panel on the bathroom door |

Thursday, 21 January 2021

Why Conspiracy Theories Survive the Failure of their Prophecies

|

| QAnon sticker available from Amazon |

John F. Kennedy Jr. is dead and has been dead for some time. In July 1999, the small plane he was traveling in crashed off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard, killing him and two others. The bodies of Kennedy and his fellow passengers were found five days later in the Atlantic Ocean. This is the version of events most people know to be true. But, in the world of QAnon, things happened a bit differently: JFK Jr. survived an attempt on his life by the so-called “Deep State” and will soon return to exact revenge and help Donald Trump fight back against a globally active cabal of satanic pedophile elites that’s responsible for all the evil in the world.

The QAnon worldview is particularly prone to these sorts of predictions, and many adherents eagerly anticipate earth-shattering future events that will completely change the world, from “the Storm” (a near future apocalyptic realization when members of this evil cabal will be arrested) to the “Great Awakening” (a time when the general population will come to realize that they’ve been lied to for decades). Years of research into millennial movements and how they survive the often-inevitable failures of these prophetic pronouncements make clear that most movements, as we outline below, can survive these failures as long as certain conditions are in place. QAnon is no different.

The fact that JFK Jr. didn’t come back on Saturday October 17th at a Trump rally, is only one of many QAnon “prophecies” that haven’t come to fruition: Hillary Clinton has not been arrested, high profile elites have not been killed or sent to Guantanamo Bay, the hundred thousand sealed indictments were not released, and the promised Golden Age has not been delivered. And yet, the movement continues.

Surviving the failure of prophecy

Many researchers read these stories and point to a classic work by social psychologists Leon Festinger, Henry Riecken, and Stanley Schachter published in 1956: When Prophecy Fails. In the book, Festinger and his colleagues provide readers with an account of a small religious group they call “the Seekers,” whose leader, Marion Keech (a pseudonym), predicted the destruction of the entire United States in a great flood on December 21, 1955.

The Seekers, though, would be saved from this destruction by aliens who were communicating with Keech telepathically. On December 21, as midnight came and went with no spacecraft, many of the members wept and sat in disbelief. Then Keech received a message from the aliens: the apocalypse had been called off. As Festinger and colleagues write, “This little group, sitting all night long, has spread so much goodness and light that the God of the Universe spared the Earth from destruction.”

This final message was just what the group needed. While common sense may suggest that in the face of such an obvious prophetic failure, the group would have crumbled and the leader abandoned and ridiculed, this is not what happened. The final message communicated to Keech convinced the Seekers that all their work was not in vain; rather, it was precisely their preparations and commitment that saved humankind from cataclysm.

From this case study of the Seekers, Festinger developed what he called the theory of cognitive dissonance. Put simply, the theory asserts that people are uncomfortable holding inconsistent beliefs and ideas at the same time and are driven to reduce this discomfort. It should be noted that Festinger is not stating that reducing this discomfort is a preference. It isn’t something we wish to be the case; it’s a drive that will happen. As Joel Cooper put it, “people do not just prefer eating over starving; we are driven to eat.”

One of the things that the Seekers did after December 21 was also something counter-intuitive: they began to proselytize. Once the initial cognitive dissonance had been reduced by the idea that their actions had saved the world, they sought to solidify this new sense of consistency by seeking validation from the outside world.

When Prophecy Fails has faced some criticism for its methodology, but as Lorne Dawson points out, “on the whole the record shows that Festinger et al. were right to predict that many groups will survive the failure of prophecy. Why they survive is another matter. The reasons are much more complicated than When Prophecy Fails implies.” Festinger and his colleagues placed a lot of emphasis on proselytization as a key mechanism by which cognitive dissonance is reduced following prophetic failure. But research over the last several decades has added at least two more strategies: rationalization and reaffirmation.

Rationalization is now seen by researchers as the most important factor in whether a group survives prophetic failure. Groups can do this in at least four ways:

- Spiritualization: the group states that what was initially thought of as a visible, real-world occurrence did happen, but it was something that took place in the spiritual realm.

- Test of Faith: the group states that the prophecy was never going to happen, but is in fact a test of faith: a way for the “divine” to weed out true believers from those unworthy.

- Human Error: the group argues that it’s not the case that the prophecy was wrong, but that followers had read the signs incorrectly.

- Blame others: the group argues that they themselves never stated that the prophecy was going to happen, but that this was how outsiders interpreted their statements.

The third strategy—reaffirmation—is also one used by several groups discussed in previous research. In this approach, the group brushes aside the failure of prophecy and reaffirms the value of the group, the benefits of membership, and doubles down on the importance of their journey on the path of truth.

According to Lorne Dawson, the body of research on failure of prophecy notes that these three strategies are most successful when at least six conditions are present:

- In-group social support: the need to move on beyond the failure of prophecy is valiantly supported by others in the group.

- Decisive leadership: the leader does not “pause in confusion in the face of failure” but provides a confident and coordinated path forward.

- Sophistication of ideology: the prophecy is robust enough that the failure of one prophecy does not dismantle the entire edifice.

- Vagueness of prophecy: the predictions are vague enough to be rationalized away.

- Ritual framing: rituals are used to not only rationalize the failure but also purify the believers and reaffirm the value of the group.

- Organizational factors: different kinds of organizations or networks will be impacted differently by prophetic failure.

Below, we use the JFK Jr. case study to elucidate how QAnon followers have dealt with this failure of prophecy and point out that similar mechanics may be deployed by followers as other anticipated events in the future similarly fail. These insights will also be important for understanding how followers react to the potential electoral defeat of President Donald Trump, whom they consider to be a savior in the White House.

When JFK Jr. didn’t come back

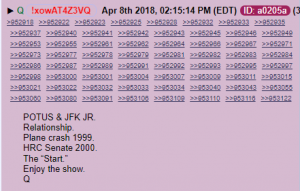

Screenshot of Qdrop 1082, from the 8kun board where “Q” posts (the string of numbers are Q’s previous messages he is replying to) , hinting at a link between JFK Jr.’s plane crash in 1999 and Hillary Clinton’s run for Senate in 2000.

In 2018, QAnon adherents became convinced that Q, whose identity remains a mystery, was JFK Jr. This conspiracy theory began in April 2018 following Qdrop 1082 [image left], which is a reference to the Clinton body count conspiracy. This was then followed by another Qdrop containing a 1956 memo from the CIA’s public website. The CIA document had nothing to do with the Kennedys but contained a reference to “guided missiles.” For QAnon adherents, this was a hint from “Q” that JFK Jr’s plane was shot down with a guided missile to make way for Hillary Clinton’s political career, which started with a U.S. Senate run the year after the plane crash.

While this theory makes no logical sense, considering JFK Jr. was not a politician and never seriously considered becoming one, for QAnon adherents the Clintons and the ‘Deep State’ considered him a great enough threat that he was worth killing to make way for Hillary Clinton’s political career.

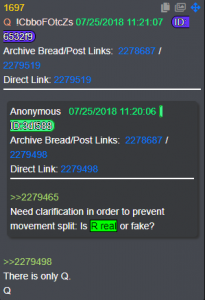

Screenshot of Qdrop 1697, from a Qdrop aggregator Where “Q” repudiates “R.”

The JFK Jr. conspiracy theory picked up steam in July 2018, during Q’s first long lull in posting. Mike Rains, who hosts the Adventures in HellwQrld podcast, told us that in the 20-day gap between Q posts, “an Anon who called themselves R took up the slack of posting about the great struggle between the Patriots and the Deep State. R made it clear that JFK Jr. was working with Trump to defeat the Deep State.” Q never engaged R on these claims, but when Q engaged in an 8Chan Q&A on July 25, 2018, they flatly denied that JFK Jr. was alive [image right].

According to Rains, this caused a lot of division in the QAnon community. The influential QAnon documentary, “The Fall of the Cabal” even ends with the claim that JFK Jr. is still alive, and that Q is merely using disinformation as a tool to protect him. Although two more Qdrops have appeared insisting that Q is not JFK Jr. and that JFK Jr. is dead, it’s had little impact on some QAnon adherents.

So why has this conspiracy stuck with QAnon adherents who usually hold Q’s word as gospel? Travis View, conspiracy theory researcher and co-host of the QAnon Anonymous podcast, told us:

“The belief that JFK Jr. is alive and will reveal himself soon is typically an extension of the belief that his father President Kennedy was assassinated by the deep state. This is seen in the claims from some QAnon followers that JFK Jr. is returning to avenge his father’s death. QAnon promises followers ultimate justice for those who have been harmed by the secret puppet masters of conspiracy theory lore. Those who believe that JFK Jr. lives simply assume that this promise extends to the tragic and traumatic deaths of JFK Jr and JFK. On top of that, these QAnon followers seem irresistibly drawn to the classic trope of a son reappearing to avenge his father’s death.”

In QAnon Telegram chats, after JFK Jr. did not return as predicted on October 17, 2020, the response was varied, but largely fell into the “human error” and “blame others” categories discussed above.

QAnon adherents stated that the JFK Jr. conspiracy theory was a deep state plot that was put in motion to discredit QAnon and the work they’re doing. As one post noted:

“Anons have gone way off base and they’re using it to make us look stupid. I personally prefer to stick with 3 years worth of hard evidence of government corruption and malfeasance on every level…things we CAN prove.”

Another post made a similar point, noting:

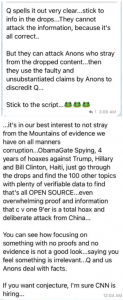

“Q spells it out very clear…stick to info in the drops…They cannot attack the information, because it’s all correct.. But they can attack Anons who stray from the dropped content…then they use the faulty and unsubstantiated claims by Anons to discredit Q…”

Screenshots from QAnon Telegram Channels reacting to the failure of the JFK Jr. prophecy.

In other words, adherents argued that some followers had strayed from the path of truth and were now dabbling in ideas that were hurting the cause. This argument was used to rally the true believers and reaffirm their commitment to Q and the “authentic” Qdrops. This is what QAnon adherents perceive as gospel, built upon three years of “evidence.”

It was also argued in some cases that those QAnon followers that were amplifying the JFK Jr. conspiracy theory might have been plants by the deep state. All in all, there was a real push for a reaffirmation of the movement, the cause, and a call for a return to the original source of insight: the Qdrops.

The future of QAnon

One of the main questions that QAnon researchers continue to wrestle with is how the movement will carry on after the election. With President Trump being seen as the savior of the republic in the White House, one who’s poised to usher in the collapse of the deep state, his defeat in the election could very well be seen as the ultimate failure of prophecy. As such, the theoretical framework presented above is important to keep in mind once the election is decided.

If Trump loses the election, we foresee potentially three responses from QAnon followers:

First, there could be instances of violence, as followers undertake an urgent campaign to bring about the arrest of supposed corrupt elites, celebrities, and the deep state as a whole. The defeat of Trump could be interpreted as a major lost opportunity to save enslaved children and to save the country—one that cannot be abandoned without a fight.

Second, we may see factionalism in the movement, with some followers being siphoned off into other movements and groups and continuing their activism in ways that become only loosely tied to QAnon.

Third, we may see the movement carry on as if nothing has changed. Many of these followers may instead be rejuvenated in their quest, arguing that, as their ally in the White House has been defeated, they need to come together and fight harder than ever before; that the movement is older and bigger than Trump himself, and it’s now up to them to carry the torch.

The path forward for QAnon followers is unclear. Their rise to mainstream visibility depended heavily on the current political climate, with the President of the United States amplifying their message and refusing to denounce them in public. If Trump is defeated at the polls, and adherents lose this megaphone, we can only hope that these baseless and ridiculous ideas don’t continue to taint our public discourse in the new year. If they do—as we expect them to, in some form at least—you’ll have an answer for the pundits who will repeatedly ask why they still believe even after the prophecies failed to come true.

A very good summary of the QAnon conspiracy theory can be found here

See also Trump - The Big Lie and How To Do It

Sunday, 17 January 2021

Favourite Gardens - Redenham Park

|

| Redenham Park |

Redenham Park, west of Andover, is an C18th Georgian house built for the Pollen family (Richard Pollen, was an old friend from the Meon Valley) and was also home to the Hambro's until it was acquired by Sir John Clark, the industrialist, famous for his long battle with Sir Arnold Weinstock. His widow, Lady Olivia Clark has created a beautiful garden behind the house over the past 40 years, notably for its huge yew hedges and topiary It's fortunately open for the National Gardens Scheme once or twice a year.

|

| Lady Olivia Clark |

Sunday, 10 January 2021

The Mystery of the Plaque and the Severed Head

|

| The Mystery Plaque |

This plaque, which stands on a table on the loggia at Old Swan House, lead to the following correspondence between Guy Boney, another friend and me in January 2021:

'Guy, I trust that your ‘A' Ladder schooling is equal to the task of identifying this chap - and the remains of the chap who’s head he’s holding - both of whom whom rest on a bas relief cast on a plaque in my loggia. The main character appears to be a satyr - or might even be the great god Pan, judging by his hairy withers - but my ‘B’ Ladder and Graham Drew schooling fails me when it comes to identifying the allusion. Perhaps the animal skins draped over his left arm are the key. Anyway, your thoughts are awaited with interest'.

To which Guy replied:

'Hm, v. interesting.

The bloke with the hairy withers is undoubtedly Pan - Greek god of flocks, shepherds etc.indeed god of everything connected with the countryside and pastoral stuff, including hunting. My long-unthumbed classical dictionary says he is usually represented as a sensual being with horns and goat’s feet, sometimes in the act of dancing - the lump in his forehead I think must be intended to represent a horn/antler, and he has something like a shepherd’s staff tucked away somewhere into his kit. The tails of the cat(s) or whatever the headed animal is illustrate his interest in hunting, pastoral activities and so on. All pretty clear so far.

I think the interesting bit is the identity of the apparently beheaded character. I think the answer is Socrates, which is partly wild guess, partly a memory of having seen a bust of him (Roman, not Greek, so 4-500 years after his death) somewhere or other. But his main characteristic (apart from a reputation for wisdom - put about in a big way by Plato in the Republic and the series of Socratic dialogues written by Plato, e.g. the Crito which we did exhaustively up to the head man) was of physical ugliness - “in features he is represented as having been singularly, even grotesquely, ugly with a flat nose, thick lips and prominent eyes”, says my dictionary, and you can see he's hardly Greek god material as shown in your stoneware.

He died in 399 BC at the age of about 70 i.e. right at the end of the Peloponnesian War and at the end of the golden fifth century which saw the building of the Parthenon (450 BC), the plays of Aeschylus and the comedies of Aristophanes. Aristophanes, always good for a satirical laugh, took Socrates apart in The Clouds, in rather the same way as W.S.Gilbert took apart Oscar Wilde in Patience by caricaturing him as the poet Bunthorne (“…if you walk down Piccadilly with a poppy or a lily in your medieval hand…And everyone will say as you walk your flowery way….”).

Poor old Socrates meanwhile was condemned after a trial in 399 to death by drinking hemlock. He had come badly unstuck by becoming involved in Athenian war politics and making an enemy of the wrong person (lucky he didn’t try his luck on Stockbridge Parish Council, but the result wd probably have been the same). He was charged with impiety and not worshipping the gods of the city (chief amongst whom was Athena - sounds like a stitch-up already), and with introducing new deities and also of being a corrupter of youth. I don’t think, btw, that last bit implies the usual thing, i.e. he doesn’t seem to have been an enthusiastic shirt-lifter (and I can’t find the classical Greek for that), but he was friendly with one or two people who were, mainly a character called Alcibiades who brought a number of people down.

To get away from fascinating C4BC Athenian gossip and back to the main point, I think the clues to this are the identification of Pan (a slightly disreputable god in C4 Greek terms), and the fact that Pan is holding aloft the bust of Socrates in, perhaps, apparent veneration. That would be a fine example of Socrates doing exactly what he was condemned to death for, i.e. encouraging the worship of a new, unconventional and too-exciting, non- establishment god (Pan) and having an arguably corruptive influence on the young by doing so.

There is a fair amount of speculation in all that, but you did ask for my thoughts and it does more or less hang together. An important factor of course is the origin of your piece of stoneware - is it ancient or modern? It doesn’t strike me as being a standard-issue chunk of garden-centre central-casting classical sculpture - it seems too sophisticated for that because it seems to betoken some degree of classical knowledge which nowadays no one has . It may hark back to the C19 or possibly even a grand tour C18 handout. Any ideas of where it came from? Perhaps it’s an Eve Lane special!

Best, Guy'

This was followed by this note to a friend with whom I was also discussing the plaque, and copied to Guy:

'I have at last heard from of our local classical scholar with his considered views on that rather ugly piece in my loggia, and fortunately it seems that our own education isn’t found completely wanting in that it’s

a) not something that every snotty schoolchild has doodled in his Kennedy’s Primer since Remove; and

b) might even said to be a bit of a conundrum to those who read Greek and Latin up to the head man at school (the one who was more remembered for his pretty daughter Polly than his magisterial translation of Plato’s Republic). So,

a) honour is intact, and

b) the game is still on to prove or disprove Guy’s current theory involving Pan and his veneration of Socrates.

I support his theory, tempered only by the fact that Socrates died from being made to drink hemlock, the C4th BC equivalent of a gallon of retsina, rather than being beheaded, but I will allow that this could just be a good example of artistic licence. After all, a prone body would hardly fit the design required tempt a C18th traveller - which is what I think we have here.

The piece was actually bought from a Jewish antique-dealer friend called Kuka Steiner, from whom we acquired quite a few of the more unusual pieces you can find dotted around the house, including the zebra skin that you will have almost tripped on more than once and which will probably be the death of me. He lives in France and Spain but is still a friend and in fact he was in touch over Christmas, so there it may be worth asking him to come clean about its provenance and which ancient collection he ‘acquired’ it from. As I say, my guess is that it’s the equivalent of a tourist trophy brought back by someone who took an obligatory C18th Grand Tour and was sold something more portable than the Elgin Marbles just to show his long-suffering parents that he hadn’t spent all his time among the flesh-pots of Paris, and had it mounted.

In fact, there is more - a reverse side - the design of which to my mind supports the Socrates theory as it seems to me to depict the owner of the severed head on the other side - who could be Socrates in full declamation mode - with what looks like a representation of the cave in which he was imprisoned - a curious chamber hewn out of the rock close to the Acropolis, as I recall from this photo taken when I was supposed to be doing some work down there'.

|

| Socrates's cave in Athens |

Guy's response:

Best, Guy

Monday, 28 December 2020

John Le Carre remembered by Matthew d'Ancona December 2020

David Cornwell 1931 - 2020

John le Carré was much more than the greatest chronicler of the Cold War. He saw the fault-lines in all that followed – and warned us of them till the end

“An unmitigated clusterfuck bar none.” Thus does one of the main characters in John le Carré’s final novel, Agent Running in the Field (2019), pithily summarise Brexit.

The book’s narrator, Nat, describes the Conservative government of 2018 with equal venom: “A minority Tory cabinet of tenth-raters. A pig-ignorant foreign secretary who I’m supposed to be serving. Labour no better. The sheer bloody lunacy of Brexit.”

That “pig-ignorant foreign secretary” is, of course, now Prime Minister in real life, desperately trying to extract a last-minute trade deal from the “clusterfuck” of Britain’s departure from the European Union. It is a measure of le Carré’s determined topicality that his final espionage thriller involved not only Brexit, Trump and Russian meddling in the Western democratic process, but even EU trading tariffs. How much further enmeshed with the reality of day-to-day politics could a fiction writer in his late eighties possibly have been?

To the very last, he raged against the dying of the light by remaining implacably vigilant; furious at the indignities to which his country was being subjected by bogus patriots, spiv nationalists and sloganeering charlatans.

Last year, I wrote a piece for Tortoise about le Carré’s significance as a “Condition of England” novelist: a writer who, for six decades, provided a compelling running commentary on the state of the nation, its transformations, ambiguities, and treacheries. From Suez to the sewers of today’s populist Right rhetoric, he was always observing, tracing every oscillation between hope and disillusionment.

When I learned of his death last night, I felt a sense of personal loss that was also a moment of disclosure: that, when all is said and done, he is, and has long been, the writer that I turn to most often and instinctively to understand politics, statecraft and their very specific character in this country.

As it happens, and as if to drive home the point, I had been watching an episode of Smiley’s People (1982), the second BBC dramatisation of le Carré’s novels to feature Alec Guinness as George Smiley. But my debt stretches back much further.

I can still remember my parents discussing the plot of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy when it was first published in 1974. Much too complex for a child, of course, but magnetic all the same: Merlin, Witchcraft, Gerald the Mole, Karla the Moscow spymaster, “chicken-feed”, lamplighters, the scalphunters, the Circus. What magic was this?

It is true that le Carré does not write often about politicians, and, when he does, he is scathing: see, for instance, the portrayal in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy of the minister Miles Sercombe, whom Smiley’s adulterous wife, Ann, once described (“proudly”) as the only one of her cousins “without a single redeeming feature”. Sercombe’s baldness, we are told, “gave him an unwarranted air of maturity,” an absurdity compounded by a “terrible Eton drawl” and his “fatuous Rolls, the black bedpan”.

Yet – for all his mockery of the political class itself – every one of le Carré’s 26 novels is, in some shape or form, about power and its exercise: about the endless, nuanced interaction between principles and ambition; between decency and (a favourite word) “larceny”; and – most complex of all – the extent to which foul deeds are justified by noble ends.

In this sense, he used the secret world as a stage upon which to explore both questions of national character, and the personal dilemmas confronted by those who find themselves embroiled in clandestine activity. Often, the price they pay is grievously high.

In Smiley’s People, it is a terrible role reversal that ensures the final defeat of Karla – “He controls the whole of Russia, but he does not exist” – as Smiley tracks down his long-time adversary’s mentally ill daughter to a Swiss clinic: “On Karla has descended the curse of Smiley’s compassion; on Smiley the curse of Karla’s fanaticism. I have destroyed him with the weapons I abhorred, and they are his. We have crossed each other’s frontiers, we are the no-men of this no-man’s land.”

Through the eyes of Smiley and many other characters, le Carré was a pitiless chronicler of national decline. In Tinker Tailor, the unmasked Soviet mole, Bill Haydon, tells Smiley that his own treachery was driven by a gradual recognition that “if England were out of the game, the price of fish would not be altered by a farthing”.

Given this metaphor, there is a bleak symmetry in the fact that, on the very day that the author died, government sources were briefing the media with the pathetic line that, if the EU and UK negotiators failed to reach a deal, gunboats would be deployed to “protect our fish”.

As a former officer of MI5 and MI6, le Carré had no time for traitors (he famously refused to meet Kim Philby in Moscow). But he never allowed his characters – or his readers – to take refuge in lazy jingoism. He understood that patriotism is meaningless if it lacks depth, reflection and a measure of uncertainty.

Nor was he a nostalgist: quite the opposite, in fact. The fall of the Berlin Wall awoke in him a great hope of a monumental rebuilding of the East – quickly dashed by what followed the historic events of 1989. In The Secret Pilgrim (1991), we are told of “Smiley’s aphorism about the right people losing the Cold War, and the wrong people winning it”.

Indeed, in novels such as The Night Manager (1993) and The Constant Gardener (2001), le Carré was quicker than most to foresee that the post-Cold War landscape would be inherited by a smug coalition of governments and corporations; that worship of reified “business” would infect public policy; and that the same breed of privately educated, endlessly charming Englishmen who had once defended the old order of the Empire and then the West against the Soviet bloc would smoothly switch their allegiance to this new and unaccountable cartel of states and plutocrats.

“The privately educated Englishman is the greatest dissembler on earth,” says Smiley in The Secret Pilgrim. “Nobody will charm you so glibly, disguise his feelings from you better, cover his tracks more skilfully or find it harder to confess to you that he’s been a damn fool.”

How true, yet again, that seems today, as Boris Johnson gurns his way through a crisis that will determine the trajectory of this country for decades. Not for nothing is one of le Carré’s (best, if lesser-known) novels titled Our Game (1995): a reference to Winchester College football. A fear of privileged men reducing the fate of nations to playtime runs through his work: in Tinker Tailor, Smiley imagines the mole Haydon “standing at the middle of a secret stage, playing world against world, hero and playwright in one: oh, Bill had loved that all right.”

In the end, the character of Smiley himself is le Carré’s most precious bequest to the world. He is a true public servant, reserved but never docile, unashamed of his erudition, ironic to a fault, sleeplessly aware that the world is full of lethal complexities and that those who pretend otherwise with their slogans and demagoguery are not to be trusted.

To the end of his life, le Carré understood that resilience in an age of pulverising technological and geopolitical change would require greater integrity than ever, greater wisdom, greater reflection. In Smiley, he imagined a profound form of Englishness that is worth preserving, not in spite of, but because of, its ambiguities. As Control, his mentor and boss, tells him after his first and unsuccessful attempt to ensnare Karla in Delhi: “I like you to have doubts…. It tells me where you stand.”

In le Carré’s penultimate novel, A Legacy of Spies (2017) – a coda of sorts to The Spy Who Came In From the Cold (1963), the book that made his name – Peter Guillam, Smiley’s closest disciple, tracks him down to a library in Freiburg. Unbidden, the elderly spy tries to explain why he did what he did with his life.

“I’m a European, Peter. If I had a mission – if I was ever aware of one beyond our business with the enemy, it was to Europe. If I was heartless, I was heartless for Europe. If I had an unattainable ideal, it was leading Europe out of her darkness towards a new age of reason. I have it still.”

Those final, spare words read today – amid the infantile bedlam of Brexit – less like an elegy for something unrecoverable than le Carré’s mission statement for future generations. It’s a fine one, too. RIP.